Want to do good? Here’s how to choose an area to focus on.

Targa heategija lühikursuse jaoks välja võetud tekstilõik.

Targa heategija lühikursuse jaoks välja võetud tekstilõik.

If you want to make a difference with your career, one place to start is to ask which global problems most need attention. Should you work on education, climate change, poverty, or something else?

The standard advice is to do whatever most interests you, and most people seem to end up working on whichever social problem first grabs their attention.

That’s exactly what our co-founder, Ben, did. Aged 19, he was most interested in climate change. Here he is at a rally, in a suitably artistic shot:

However, his focus on climate change wasn’t the result of a careful comparison of the pros and cons of different areas. Rather, by his own admission, he’d happened to read about it, and found it engaging because it was sciency and he was geeky.

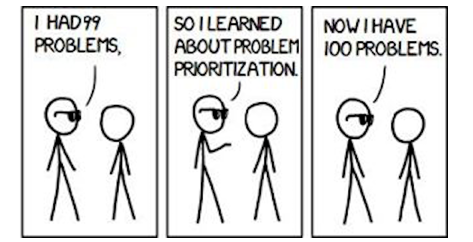

The problem with this approach is that you might happen to stumble across an area that’s just not that big, important or easy to make progress on. You’re also much more likely to stumble across the problems that already receive the most attention, which makes them lower impact.

So how to avoid these mistakes, and do more good?

We’ve developed three questions to ask yourself to work out which social problems are most urgent – where an extra year of work will have the greatest impact.

It’s based on work by Open Philanthropy, a foundation with billions of dollars of committed funds, and the – modestly named – Future of Humanity Institute, a research group at Oxford.

You can use these steps to compare areas you could enter (e.g. education or health), or if you’re already committed to an area, you can compare projects within that area (e.g. research into malaria or HIV).

We tend to assess the importance of different social problems using our intuition, i.e. what seems important on a gut level.

For instance, in 2005 the BBC wrote:

The nuclear power stations will all be switched off in a few years. How can we keep Britain’s lights on? …unplug your mobile-phone charger when it’s not in use.

This so annoyed David MacKay, a Physics professor at Cambridge, that he decided to find out exactly how bad leaving your mobile phone plugged in really is. See the story of his attempt to find out.

The bottom line is that even if no mobile phone charger were ever left plugged in again, Britain would save at most 0.01% of its personal power usage (and that’s leaving aside industrial usage and the like). So even if entirely successful, a quick estimate shows that this BBC campaign could have no noticeable effect. MacKay said it was like “trying to bail out the Titanic with a tea strainer”.

Instead that effort could have been used to change behaviour in a way that could easily have 100 times as large an impact on climate change, such as installing home insulation.1

Decades of research has shown that our intuition is bad at assessing differences in scale. For instance, one study found that people were willing to pay about the same amount to save 2,000 birds from oil spills as they were to save 200,000 birds, even though the latter is objectively one hundred times better. This is an example of a common error called scope neglect.

Rather, we need to use numbers to make comparisons, even if they’re very rough.

In the previous article, we said that social impact depends on the extent to which you help others live better lives. So based on this definition, a problem has greater scale:

Scale is important because the effect of activities on a problem is often proportional to the size of the problem. Launch a campaign that ends 10% of the phone charger problem, and you achieve very little. Launch a campaign that persuades 10% of people to install home insulation, and it’s a much bigger deal.

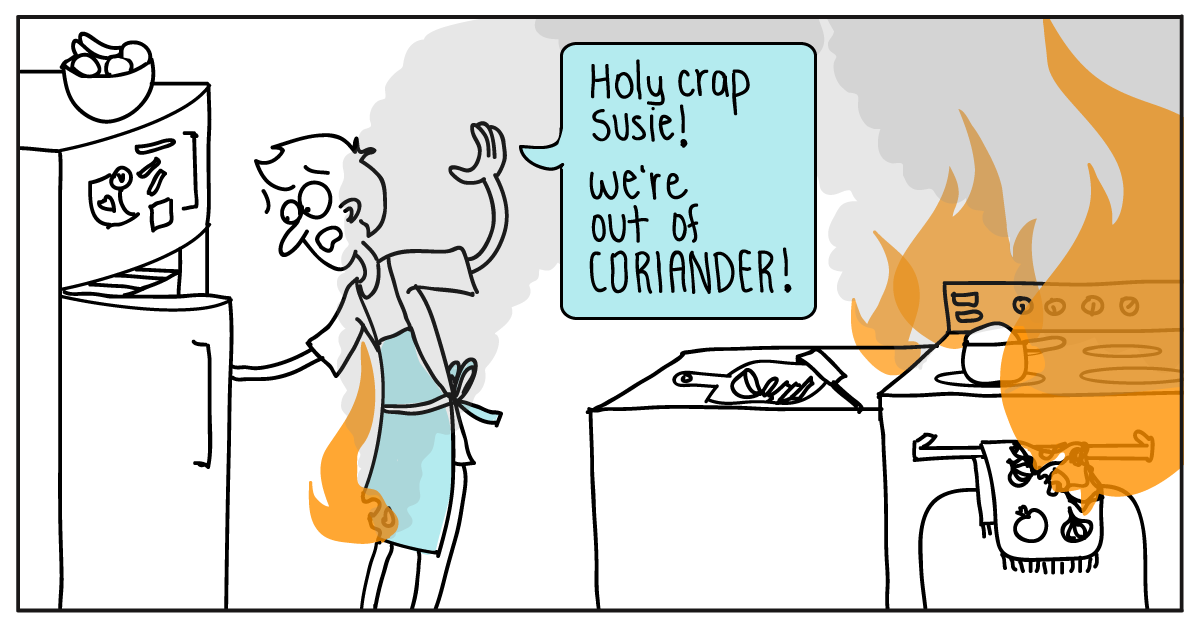

If we cared so little about the relative importance of different problems in our personal lives.

In the previous article, we saw that medicine in the US and UK is a relatively crowded problem – there are already over 700,000 doctors in the US and health spending is high, which makes it harder for an extra person working on health to make a big contribution.2

Health in poor countries, however, receives much less attention, and that’s one reason why it’s possible to save a life for only about $7,500.

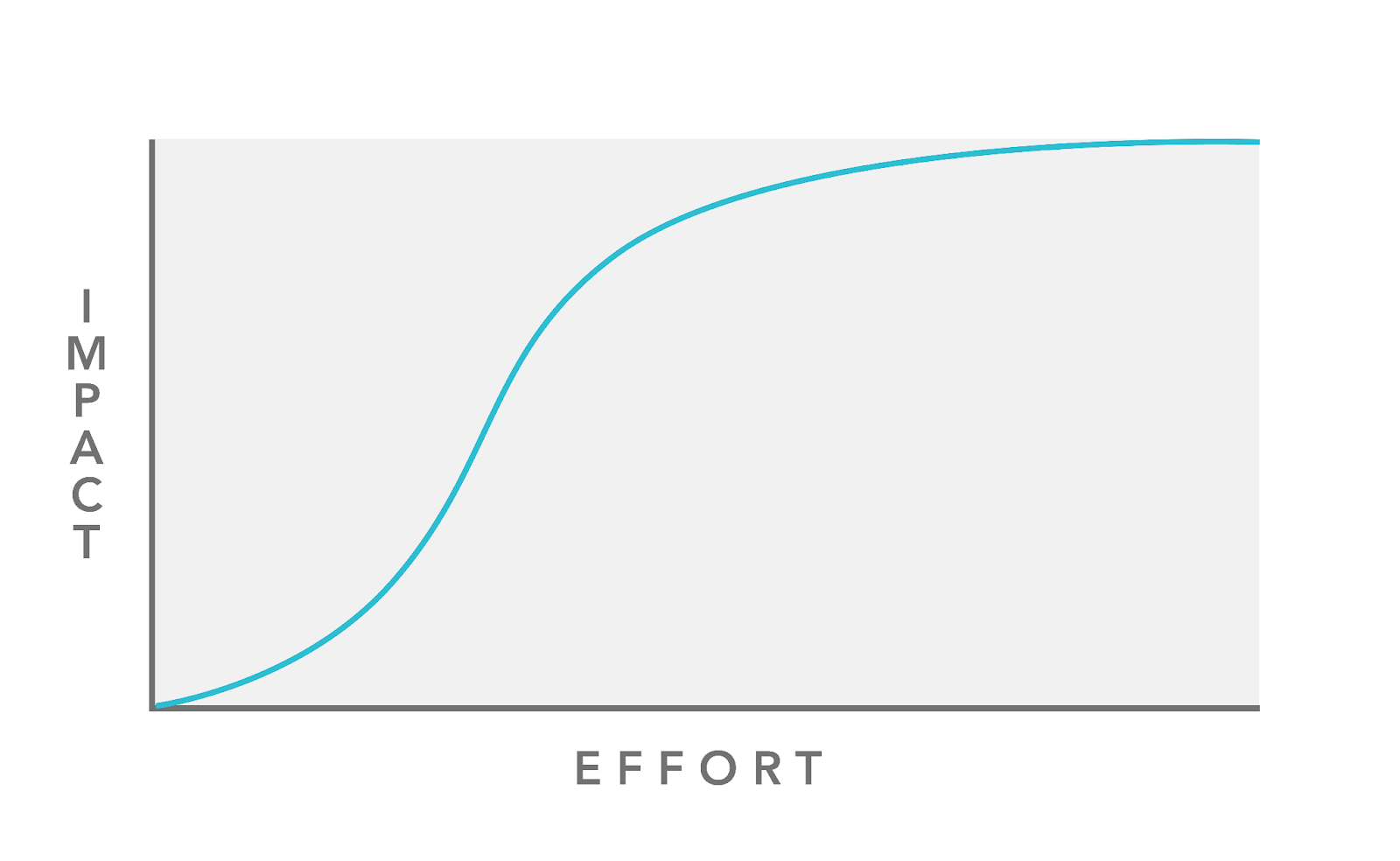

The more effort that’s already going into a problem, the harder it is for you to be successful and make a meaningful contribution. This is due to diminishing returns.

When you pick fruit from a tree, you start with those that are easiest to reach – the low hanging fruit. When they’re gone, it becomes harder and harder to get a meal.

It’s the same with social impact. When few people have worked on a problem, there are generally lots of great opportunities to make progress. As more and more work is done, it becomes harder and harder to be original and have a big impact. It looks a bit like this:

Diminishing returns to effort – it’s economics 101.

The problems your friends are talking about and that you see in the news are where everyone else is already focused. So, they’re not the neglected problems, and probably not the most urgent.

Rather, the most urgent problems – those where you have the greatest impact – are probably areas you’ve never thought about working on.

We all know about the fight against cancer, but what about parasitic worms? It doesn’t make for such a good charity music video, but these tiny creatures have infected one billion people worldwide with neglected tropical diseases.3 These conditions are far easier to treat than cancer, but we never even hear about them because they very rarely affect rich people.

So instead of following the trend, seek out problems that other people are systematically missing. For instance:

Following this advice is harder than it looks, because it means standing out from the crowd, and that might mean looking a little weird.

Okay, that is a neglected problem, but neglectedness is not the only thing you need to look for.

Lots of charitable programmes don’t work. Here’s an example in the field of reducing youth crime.

Scared Straight is a programme that takes kids who have committed misdemeanours to visit prisons and meet convicted criminals, confronting them with their likely future if they don’t change their ways. The concept proved popular not just as a social programme but as entertainment; it was adapted for both an acclaimed documentary and a TV show on A&E, which broke ratings records for the network upon its premiere.

There’s just one problem with Scared Straight: it probably causes young people to commit more crimes.

Or more precisely, the young people who went through the programme did commit fewer crimes than they did before, so superficially it looked like it worked. But the decrease was smaller compared to similar young people who never went through the programme.

The effect is so significant that the Washington State Institute for Public Policy estimated that each $1 spent on Scared Straight programmes causes more than $200 worth of social harm.4 This estimate seems a little too pessimistic to us, but even so, it looks like it was a huge mistake.

No-one is sure why this is, but it might be because the young people realised that life in jail wasn’t as bad as they thought, or they came to admire the criminals.

Some attempts to do good, like Scared Straight, make things worse. Many more fail to have an impact. David Anderson of the Coalition for Evidence Based Policy estimates:

Of [social programmes] that have been rigorously evaluated, most (perhaps 75% or more), including those backed by expert opinion and less-rigorous studies, turn out to produce small or no effects, and, in some cases negative effects.

This suggests that if you choose a charity to get involved in without looking at the evidence, you’ll most likely have no impact at all.

Worse, it’s very hard to tell which programmes are going to be effective ahead of time. Don’t believe us? Try our 10 question quiz, and see if you can guess what’s effective:

The quiz asks you to guess which social interventions work and which don’t. We’ve tested it on hundreds of people, and they hardly do better than chance.

So, before you choose a social problem, ask yourself:

If the answer to all of these is no, then it’s probably best to find something else.

(Read more about whether it’s fair to say most social programmes don’t work.)

Scared Straight showed juvenile delinquents life inside jail, aiming to scare them away from crime. The only catch: it made them more likely to commit crimes rather than less.

You probably won’t find something that does brilliantly on all three dimensions. Rather, look for what does best on balance. A problem could be worth tackling if it’s extremely big and neglected, even if it seems hard to solve.

There’s no point working on a problem if you can’t find any roles that are a good fit for you – you won’t be satisfied or have much impact.

So, once you’ve identified problems that have a good combination of being big, neglected and solvable:

If you’re already an expert in a problem, then it’s probably best to work within your area of expertise. It wouldn’t make sense for, say, an economist who’s crushing it to switch into something totally different. However, you could still use the framework to narrow down sub-fields e.g. development economics vs. employment policy.